Meeting Barbara Fea

How a wrecked ship revealed a remarkable woman

Two years ago in the February of 2024, a local lad found thick oak sticking from the sand of a beach here on the island of Sanday in Orkney. The question of its identity introduced me, by some tangent, to a remarkable story that I yearn to tell.

Sanday

Sanday is a tiny island in Orkney, shaped like a lower-case “y”, stretching just fourteen miles from tip to tip and never more than a mile in width. There’s about five hundred folk here, the majority of whom were drawn here from outwith both Orkney and Scotland. There’s maybe a hundred people whose voices are Orcadian, whose families wind back into the past for generations, but islands have always, always been places where folk come and go, while others stay.

Orkney is the first cluster of islands you touch if you follow a map from the top tip of Scotland, with Shetland our cousins to the North-East. Like Shetland, the voices, stories and histories of our islands come from both the North and the South. Before we were Scotland, we were Norse. The melody of Orcadian speech and the hospitality norms here felt so similar to that I’d found with friends from the South of Sweden.

Those Norn words have worked their way into the landscape as well as the tales told here. I’ve been here for nearly nine years and I’m always learning new words, phrases and tales whose meanings are intertwined with the place that’s now my home. The earth where I know I’ll be buried, one day to perplex archaeologists in the future.

The Wreck

The wreckage was, as the archaeologists put it: “Extremely significant.” One of very few examples of relics from the era of transatlantic trade (with all the horror that implies) and from the whaling boom. The oak planks, boards, hull, ribs, beams and even futtocks had been unusually well-preserved after sitting for centuries beneath the pale sand.

A rapid response followed: farmers helped to lift the timbers out of the destructive tide and safely away from folk taking a piece for themselves. Conservationists, archaeologists and maritime historians came to our tiny island to measure and make notes, to teach us how to wrap the oak with duvet covers and old sheets before they were wrapped in industrial cling-film and set to desalinate in a tank outside our small heritage centre.

The unanswered question was: what was this wreck?

After one meeting, I asked whether it was worth going to the archive to check their boxes of folklore to see if there might be some vestige of folk memory of a ship so large coming to its doom here on our sands.

“We rely on facts, not gossip. The dendrochronology will get us there.”

I’m not saying that I’m a gossip, but to me, that felt like a challenge.

The Archive

A couple of weeks later, I was checking my phone on the round benches outside Orkney Library and Archives, when my friend Cary sat down next to me and leaned in with a grin:

“As if I’d miss the chance to prove someone wrong!” Cary was a Greenham Common protester, working both with bolt cutters and camera to cause as much trouble as possible for the military base. I had known she would be a great ally in this.

Unfortunately, once we got up into the archives, I realised that I really had no idea what I was doing. The archivists are very familiar with this kind of situation, so they sat us down at the old computer (think Murder, She Wrote’s last couple of seasons) which has the archive catalogue.

Apart from being proud that I remembered what Boolean search terms are, I looked blankly at the hundreds of entries that mentioned Sanday and Wreck. We are, after all, an island rather notorious for ships breaking in the shallows near our dangerous shores.

The archivist said she’d fetch us a couple of books. Cary got the Sanday Church History - a fascinating book that does include lists of wrecks. I was handed The Merchant Lairds of Long Ago, a plain book with time-worn pages and a simple, soft grey cover.

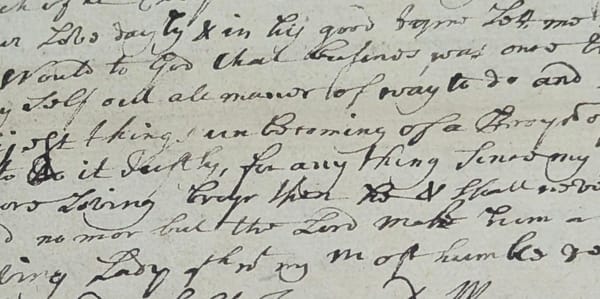

It’s a collection of letters sent between the members of the Traill family of Elsness from about 1698 to 1729, transcribed by Hugh Marwick in 1936. I flicked through the index, then went back to the introduction, which has this incredible description of Barbara Fea’s relationship with Patrick Traill:

Not long after this initial misfortune [being held to ransom by pirates], his father acquired the farm of Housby in the neighbouring island of Stronsay, and Patrick was sent over as manager. It is vain to speculate on what his life after might have been if Barbara Fea had not chanced to live on the same island; for there she was – daughter of Patrick Fea of Whitehall, a girl then in her ‘teens but possessed of such strength of mind and resolution of character that Patrick in comparison was like a silly lamb caged in with a tigress. The Feas and the Traills were old acquaintances and had been from time to time on terms of friendship and again of bitter enmity. But as luck would have it, Patrick and Barbara came together and an intimacy was established which resulted in a litigation that lingered on for two generations – smouldering for certain periods only to flare up again into fierce blaze. Not until 1776 was it finally extinguished, by which time the two original sinners had long been in their graves. Of “guid-gangin’ pleas” for which the earlier Scottish courts were notorious, surely this case must have been the record.

I laughed and then quickly hushed myself. Cary half-raised an eyebrow.

“You’ve seen something distracting?”

“Like a silly lamb caged in with a tigress?!” I was flushing with joy. “I have no idea who this woman is, but I love her.”

Cary closed the Sanday Church History.

“Looks like the wreck’s out the window!”

What was the Sanday Wreck?

We never could hope to get an exact match when all we had was wood, but, after many months of many researchers (plus me) going through court records and folders of letters in archives both here and elsewhere, we found no positive proof. All we had was a single vessel that we couldn’t disprove by age, manufacture or the English origin of the oak.

Wessex Archaeology summarise it far better than I can, and they have a wonderful video narrated by the excellent folklorist Tom Muir.

And there’s a folk tale that describes the wreck and the witch who called it to its doom. Cary was as chuffed as I was. So much for facts, not gossip.

Gossip was there all along.

A Story Barely Told

But stick with me: the story of Barbara Fea is a rollercoaster. Her court case lasted for four generations and half a century and I’m determined to tell you everything I can in what just has to become a book about her courage and tenacity in the face of a time that treated women as lesser beings and a powerful family who just wanted her dead.

Subscribe to this blog to get updates as I write more. It’ll be Barbara Fea, Sanday stories, drawings and dry-stone dyke building.

Where else will you get all of that?